|

“I am a letter, therefore I am a poet.”

Adeeb Kamal Ad-Deen

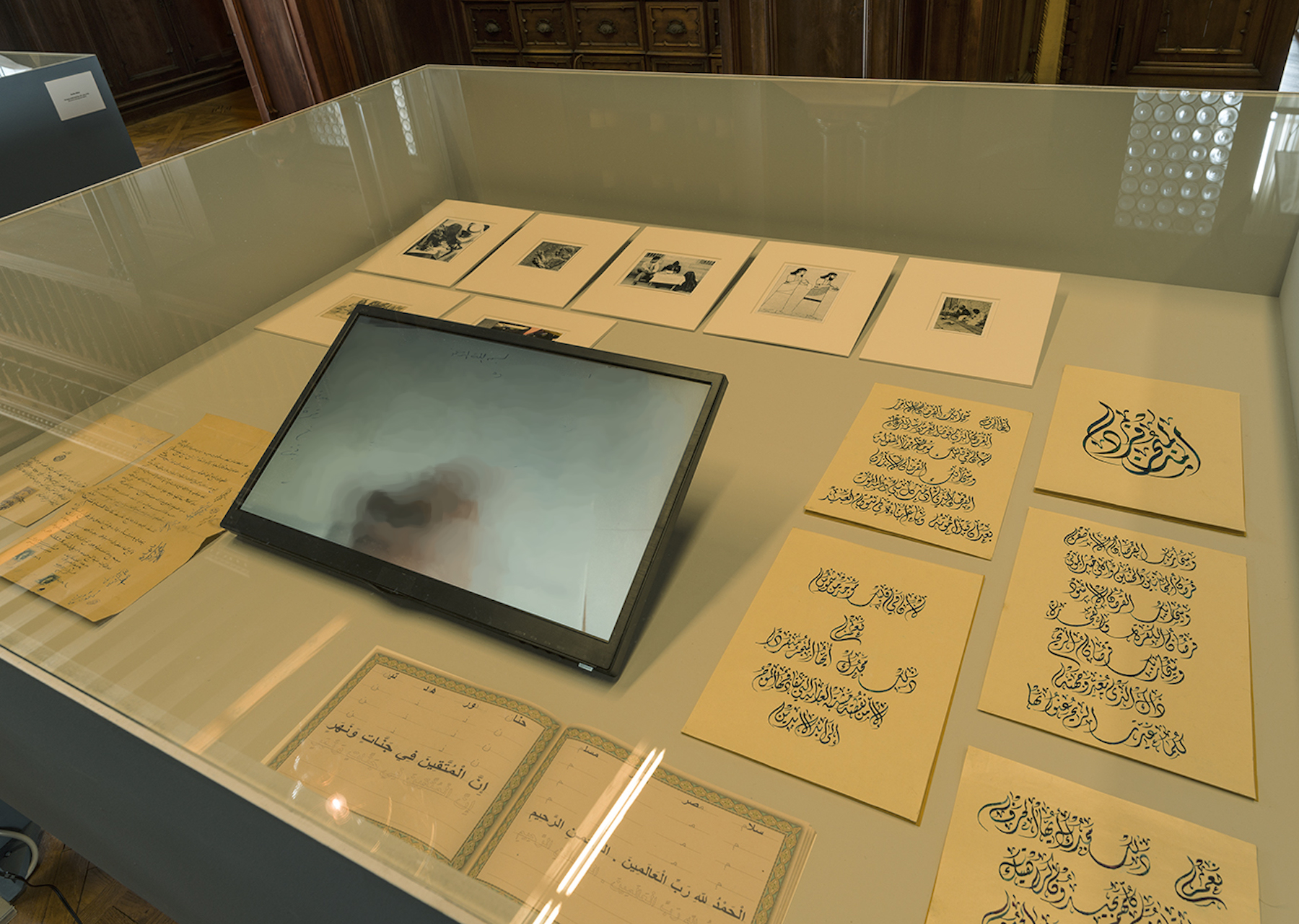

Writing is one of the seven themes of ‘Archaic,’

the Iraq Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale.

In light of this, Ruya speaks to the

Iraqi-Australian poet Adeeb Kamal Ad-Deen

(b.1953, Babel Province), whose

works weaves together Sufi mysticism and

poetry, often focusing on the letter as a

vehicle for the imagination. Kamal Ad-Deen has

published 19 poetry collections in Arabic and

English, and his work has been translated to

English, French, Italian, Persian, Spanish and

Urdu among other languages. He was awarded the

Grand Poetry Award (1999) in Iraq. His poems

appear in the anthologies The Best Australian

Poems 2007 (ed. Peter Rose) and The Best

Australian Poems 2012 (ed. John Tranter), the

Australian literary journals Southerly, Meanjin

and the Friendly Street Poets. Kamal Ad-Deen’s

poem ‘You Who Sail Alone’ accompanied one of the

artworks at the exhibition, and was translated

and published in the exhibition catalogue

Archaic.

Iraqi literature has many roots: ancient epics,

Islamic poetry, stories of djinn and demons,

oral Bedouin traditions, coffee-shop gossip,

music and contemporary urban life. How did you

find your voice as a poet?

- Poetry, as I understand it, is the attempt to

crack life’s code, to understand its secrets,

profound and fleeting, sublime and ridiculous,

and the attempt to make peace with its endless

trials. Poetry is the living mirror of all that

lives in life. It is a spark that gleams in the

deepest, darkest regions of the mind. It begins

as a response to a tear or an alarming

situation, to a wounding word or an exciting

spectacle, to a sweet song or a painful memory.

The true poet is capable of seizing on this

spark (blessed or cursed, wounded or tormented,

as the case may be) and using it to set alight

their memory, which is like dried and flammable

firewood, at which the images and words billow

out in clouds.

The letter is what sets me apart as a poet. You

might say it’s my creative identity, through

which I have expressed the tormented cries and

dreams of my soul over the course of nineteen

collections, starting with Details (Najaf: ,

1976) and running right through to my latest

book Letter of Water (Beirut: Dhafaf,

2017). In my opinion, the Arabic letter

has different “levels”: the structural, the

veiled, the indicative, the symbolic, the

cultural, the mythic, the spiritual, the

supernatural, the magical, the talismanic, the

rhythmic, and the childlike. I have written

hundreds of letter poems that embrace these

levels as a reference. These poems use the

letter both as a veil and a means to uncover

this veil, or as a tool and a means to examine

the tool. The letter is a private language with

its own symbols, signifiers and references that

unravel themselves and the language itself. I

have spent decades devoted to the letter, so

that it has become my destiny, which binds me

and will bind me till the end. So that’s why I

can say: I am a letter, therefore I am a poet.

In your poem ‘You Who Sail Alone’ you compare

the letter to a passing ship, and the dots on

these letters as a ‘new sea the pirates cannot

easily sail’. Could you expand a little on these

images?

- My approach to the letter varies in all my

poetry – not just the poem presented here. In

Sufism the dot or point represents Being, the

centre of the universe and the Greater World. As

a poet, I also reference the dot’s other

meanings, not only through Sufi symbolism. In

many of my poems the dot is a centre or seat for

the heart, the soul, the body and perception.

What distinguishes my own experiments with

letters from ancient Sufi literature, is that

the Sufi approach is primarily an intellectual

one (and occasionally a talismanic one) only to

be understood by the most elevated initiates. I

worked hard to make my approach poetic by

deploying concrete imagery, since I believe that

intellectualism in this sense is one of poetry’s

bitterest enemies. I also work to ensure that it

is accessible to everyone without, at the same

time, losing the initiates (or even the most

elevated initiates). Therein lies the aesthetic

challenge: the poetic/philosophical aspect of my

lettering experiments. As for the letter, it is

the vehicle for the miracle of the Quran, which

is the beginning and end of knowledge.

It seems that you’ve built a world out of

letters, how do you imagine this world to exist

visually?

-The letter is my identity: spiritual, artistic,

aesthetic, overt and secret. It appears in my

poetry in a variety of images and in numberless

forms: as the lover and the beloved, the king

and the vagrant, the guide and the lost, the

wise and the gone-astray, the ascetic and the

sybarite, the learned and the wrong, the saint

and the madman, the one who remembers and the

one who forgets, the contemplative and the

boisterous, the old man and the child, the man

and the woman, the voice and the echo, the soul

and the body, peace and war, the executioner and

the victim, the distant and the near at hand,

and so on.

The earliest known examples of writing originate

in Mesopotamia, but in modern-day Iraq some 20%

per cent of the population are illiterate. What

role can writers (or poets) play in the Iraq of

today?

- The duty of the poet wherever they come from,

not just Iraq, is to hold up a mirror to the age

they live in, otherwise they become a false

witness. They have to address the major problems

of human existence, such as love, loneliness,

war, death, hunger and ignorance, in order to

shed light on their deepest depths and limitless

fine detail. The poet must point to where the

terrible flaws are, those areas where humanity

currently speaks only the language of hate,

prejudice, violence, extremism and exclusion—the

very opposite of hope, love, beauty, the right

to education and a happy life.

First and foremost, poetry is a purely aesthetic

message, but through the translucent,

unblemished, dazzling curtain of beauty we

perceive the poem’s spiritual message, which

facilitates a profound and true search for all

that is radiant in life. Poetry lends readers

powerful assistance in their fight against

darkness, backwardness and ignorance in all its

many shapes and forms, whatever it may be

called.

Your poems have been translated into a number of

languages. What challenges do your poems present

to the translator, in your opinion?

- A poet is the best person to translate poetry.

Translating poetry requires an understanding of

the poetic techniques employed all over the

world, and a genuine understanding of the

poetics of the two languages being translated.

When the translator selects words and composes a

translation, they should preserve the spirit and

poetry of the original as much as possible. In

my work as a translator, I focus on work which

is built around “themes” rather than dissonances

in language and word games. That is because

“themes” overcome many difficulties of the

translation process, retaining the delicate skin

of their artistry intact. As for poetry that

relies primarily on language games, there is

absolutely no way this can be translated

You who sail alone

Adeeb Kamal Ad-Deen

O letter,

the Red Pirate shall fight you, the

pirate who

tore down the throne and gave it

to the rabble

because your heart harbours

a wave of childhood moons.

And the Blue

Pirate shall fight you, the pirate who

pushed

everything into death’s whirlpool

having

murdered his brothers

and sold his sons in

the slave market,

because your heart harbours

a wave of suns.

And the Yellow Pirate shall

fight you,

pirate of the mad, effete,

and

those who eat the bodies of the dead.

The

Black Pirate shall fight you,

pirate of the

wicked unbelievers.

The Pirate of the Wind

shall fight you, he

who changes his course

as the wind changes its name.

Yes,

this is your glory, O letter;

all the

pirates hate you easily

because you proposed

a point

for beauty and for love

and tried

to form

if only in imagination

a new sea

the pirates cannot easily sail.

Yes,

this

is your glory, you

who sail alone

save for

your point: your bare wood

thrown back and

forth by the waves

for all eternity.

***************

Published in Ruya

Foundation’ website

in

Novembr 3, 2017

https://ruyafoundation.org/en/2017/11/themes-archaic-4

|